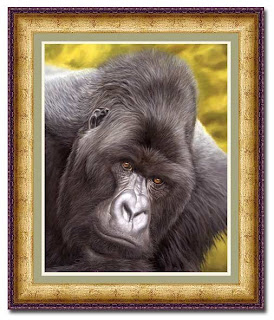

Good advertising brings your attention to things you want to know. One day I looked up at the top of my blog, and saw an ‘ad’ I immediately liked. It was a detail of the work above. You see, I belong to Culture Pundits, a network of art blogs and artists who display ads related to the arts (and for some reason Tekserve). Serendipity! I can’t think of the last time an ad showed me anything of interest, much less introduced me to a new artist.

Good advertising brings your attention to things you want to know. One day I looked up at the top of my blog, and saw an ‘ad’ I immediately liked. It was a detail of the work above. You see, I belong to Culture Pundits, a network of art blogs and artists who display ads related to the arts (and for some reason Tekserve). Serendipity! I can’t think of the last time an ad showed me anything of interest, much less introduced me to a new artist.

Idiotically, I did not click on the ad. So I had to do some sleuthing to find artist Tara Giannini‘s website and more of her intricate, layered panels. I can’t decide if they would fit better in a Regency mansion or creepy junkshop. Apparently, the artist had something similar in mind, stating that she tries to find the line between ugliness and beauty.

Idiotically, I did not click on the ad. So I had to do some sleuthing to find artist Tara Giannini‘s website and more of her intricate, layered panels. I can’t decide if they would fit better in a Regency mansion or creepy junkshop. Apparently, the artist had something similar in mind, stating that she tries to find the line between ugliness and beauty.

Based in Brooklyn, Giannini describes her work as exploring “the implications, limitations and individual perceptions of taste, beauty and excess in both art and culture, while simultaneously exploring my interests in overindulgence, visual complexity and ornamentation. It is a romantic and celebratory exploration into personal ideals of the beautiful, and the play that exists between the natural and the artificial.”

Based in Brooklyn, Giannini describes her work as exploring “the implications, limitations and individual perceptions of taste, beauty and excess in both art and culture, while simultaneously exploring my interests in overindulgence, visual complexity and ornamentation. It is a romantic and celebratory exploration into personal ideals of the beautiful, and the play that exists between the natural and the artificial.” I love the thickness of the paint and lushness of the materials. While these works don’t quite have that creepy air of Victorian dolls, Giannini takes the same neo-Baroque, over the top aesthetic and pushes it until it’s on the cusp of breaking down. It’s interesting and sensual in an unpleasant way.

I love the thickness of the paint and lushness of the materials. While these works don’t quite have that creepy air of Victorian dolls, Giannini takes the same neo-Baroque, over the top aesthetic and pushes it until it’s on the cusp of breaking down. It’s interesting and sensual in an unpleasant way.

This kind of detailed, 3D works is better appreciated in person, especially for grasping scale, but sometimes you just know you like something, right?